About

St. Louis Shag is an up-tempo partnered swing dance that emerged in St. Louis, Missouri during the mid-1930s.

The primary step is an eight-count basic done side-by-side, which is augmented by rhythmic variations using kicks, stomps, cross-overs, quick steps, and brush-steps. Skilled partners will change positions from side-by-side to open, hand-to-hand, back-to-back, and front-to-back positions, as well as break away from one another. Historically, St. Louis Shag was not a stand-alone dance, but an element of the wider Lindy Hop or jitterbug styles featuring swingouts and acrobatics. As a derivative of 1920s partnered Charleston, Shag draws from African-American dance traditions that became an increasingly key aspect of nightlife in urban areas during the early 1900s. Shag dancers value individual expression and lead and follow teamwork.

If you would like a more in-depth description of St. Louis Shag please check out our history section.

Music for St. Louis Shag

St. Louis Shag can can be danced to a variety of up-tempo jazz and swing styles. If you are looking for music to dance St. Louis Shag to check out this curated list or this Spotify playlist!

Recent Posts

-

When the Big Apple Came to St. Louis

by Christian Frommelt

Albert Murray writes that innovations in jazz music have far less to do with originality, and much more to do with how musicians use counterstatement and variation through existing conventions. What Black dancers in South Carolina did with existing conventions is precisely what made the Big Apple so electrifying to the dancing public in 1937. Not since the Charleston years had a dance held such a capacity to merge exhibition with social participation. The Big Apple possessed siren-like echoes of past dances, from recent Prohibition-era favorites to the African-derived ring shout of coastal Carolina and the square dances of the 19th century. Ballroom instructors and theater managers sought to capitalize on the craze, and the Big Apple, although not enduring, became a huge popular culture reference. The Big Apple’s biggest impact may have been reinforcing the prominence of existing dances and generating a new enthusiasm for “shag” dancing in places like St. Louis.

A Called Dance

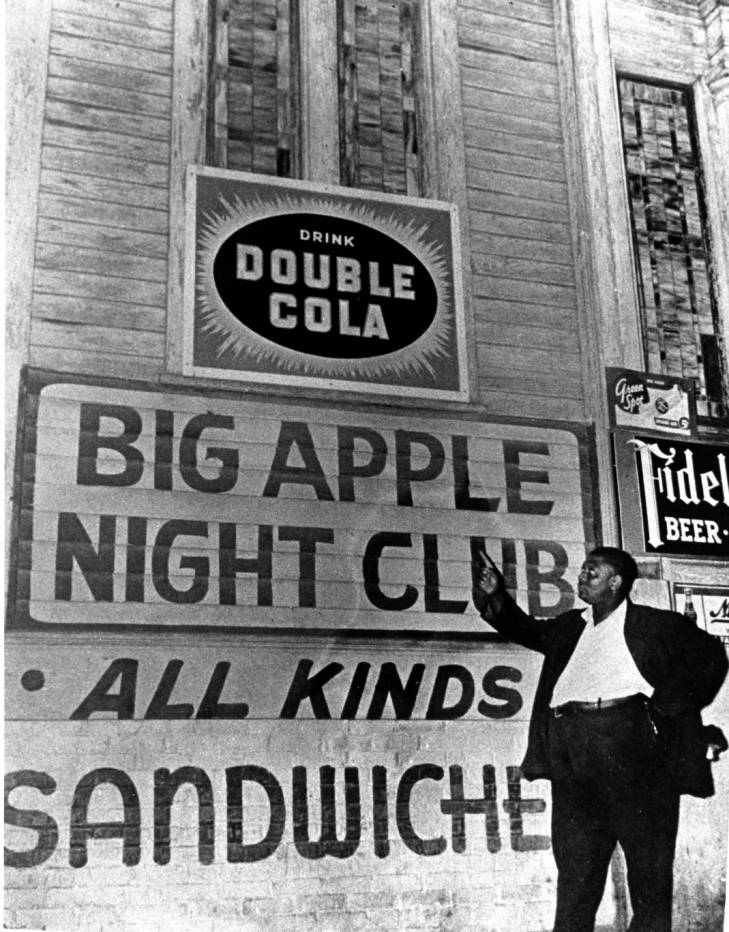

To go to the beginning, or at least a beginning, we must travel to Columbia, South Carolina in 1936 and enter the Big Apple Club, an obsolete Jewish synagogue converted into a Black nightclub managed by Elliot Wright and Frank “Fat Sam” Boyd. Where Orthodox Jewish men had prayed in rows of pews, Black youngsters now held their Saturday night functions. Some nights the club was so full that a queue formed outside of the front door. In a 1937 newspaper article, the 20-year-old Boyd states that clubgoers had been doing the slow drag and one-step for a long time, and that he decided to “step things up lively,” with new figures, which he called by number and were danced by 18 of the club’s expert dancers. According to the article, the figures included Truckin’, Suzie Q, the Charleston, as well as some apple-themed steps, such as “carvin’ the apple,” which involved a series of crisscross steps and fast shuffling.

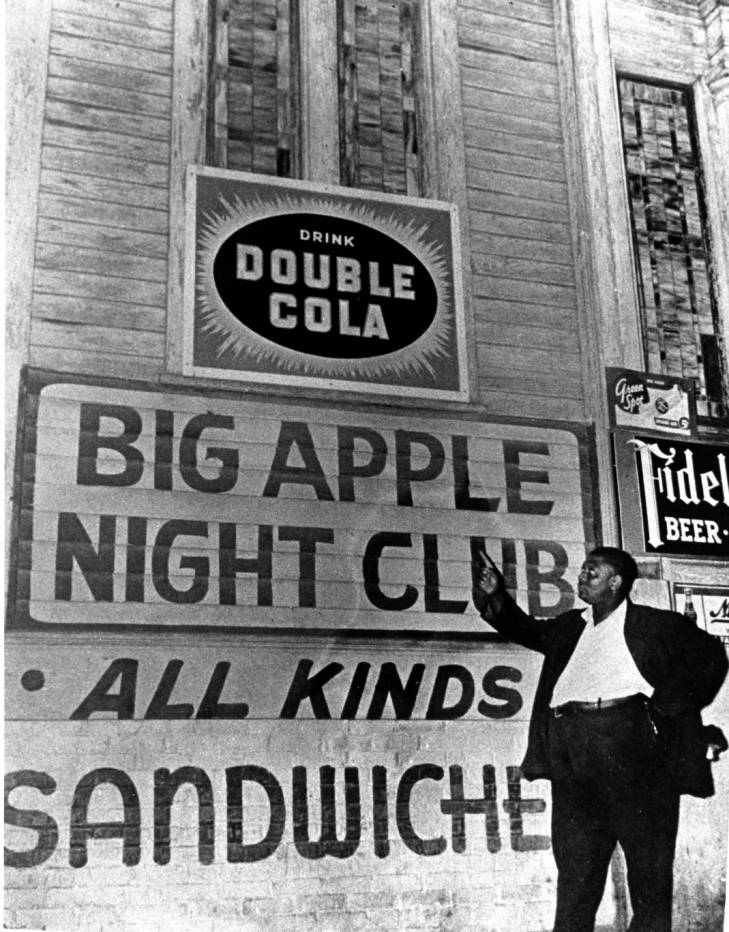

Manager Elliot Wright at the Big Apple Club in Columbia, South Carolina. Group dances that required a caller were widely practiced by Americans of all ethnicities leading up to the 20th century. White ballroom instructors were eager to point out the connections between the Big Apple and traditional European square dances, but African-American dancers had a long-standing tradition of stylizing cotillions, quadrilles, and contradances, which remained popular during the ragtime era. Black professional “set-callers” became reputable for inventing new systems of set-calling and performing original solo steps. When Wright developed new figures to call at the Big Apple Night Club, the convention of calling dances was likely as idiomatic as the old one-step and slow drag.

As an adjacent thought about called dance traditions, I can’t help thinking of how legendary jazz dancer Frankie Manning would call out the steps of the Shim Sham routine on a floor full of swing dancers. The fact that most had memorized the routine didn’t matter. The way he called the steps enlivened a new sense of how they should be executed. The eagerly anticipated “slow motion” and “freeze!” calls during the free-for-all portion of the routine forged new creations only partially within one’s control.

From the Big Apple Club to the White House

The version of the Big Apple that quickly spread to white coastal beach resorts in the spring of 1937, and then on to large stages and ballrooms in New York, was a version as imitated, interpreted, and adapted by white teenagers. Elliot Wright allowed Billy Spivey, Donald Davis, and Harold Wiles to sit in the balcony, where they could watch the dancers. It was a microcosm of the legally enforced racial modus operandi that allowed white dancers to siphon off Black dances into spaces of opportunity to which white folks alone were privileged. Soon enough entertainment scouts began holding contests and staging the Big Apple at grand theaters like the Roxy and across the vaudeville circuit. By the end of 1937 the Big Apple had been performed by 500 children at the White House, where President Roosevelt claimed that it “lacks rhythm.”

In many ways, the Big Apple’s newness was merely in its name-branding. Wright told the Aiken Standard in August 1937 that “We call it a swing dance, the white people call it the Big Apple.” And the Pittsburgh Courier describes an already-familiar lexicon of Harlem jazz dancing:

“you break right into the good old Charleston–After a bit of that you catch the ork [?] on the down beat and switch gracely into the ‘Black Bottom’–then grab your armful and go to town via the Lindy Hop route;–but not for long because the Shag comes next and as if that isn’t enough ya jam it with a bit of the Suzi-Q that was the thing just last season ago–Then not to miss anything ya sweet-on it with just so much of the ‘Truck.’ After that you should be good and tired and down to the very core of the ‘Apple,’ so ya . . . glide into a bit of fox-trot . . . . If [you] can think up any other steps, add them also for according to the best authorities on the subject . . . anything goes when you’re doing the ‘Big Apple.’”[2]

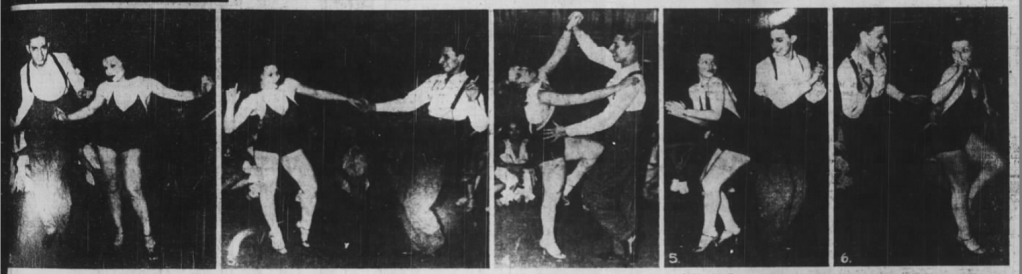

Big Apple steps demonstrated by bandleader Willie Bryant and Amy Spencer, Pittsburgh Courier. In other words, in the context of swing, the Big Apple was everything and the kitchen sink, incorporating favorite steps like Truckin’, classics like Black Bottom, but also leaving room for new inventions of rhythmic movement, spatial configuration, and imitation with steps inspired by boxer Joe Louis and tap dancer Fred Astaire. The key ingredient of “shining” required individuals to bring their own style, creativity, or imitation to the benefit of the group, an element of the jam circles made legendary by the lindy hoppers of the Savoy Ballroom. It’s fitting then that Frankie Manning’s Big Apple choreography featured in the 1939 film Keep Punchin’ enshrined a temporary dance fad into the enduring story of jazz dance.

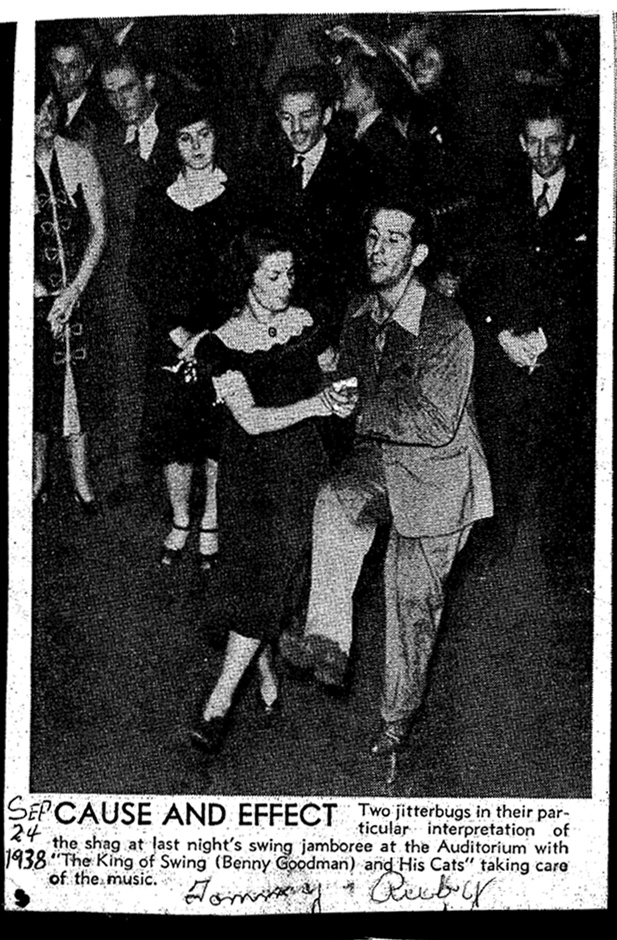

When the Big Apple Came to St. Louis

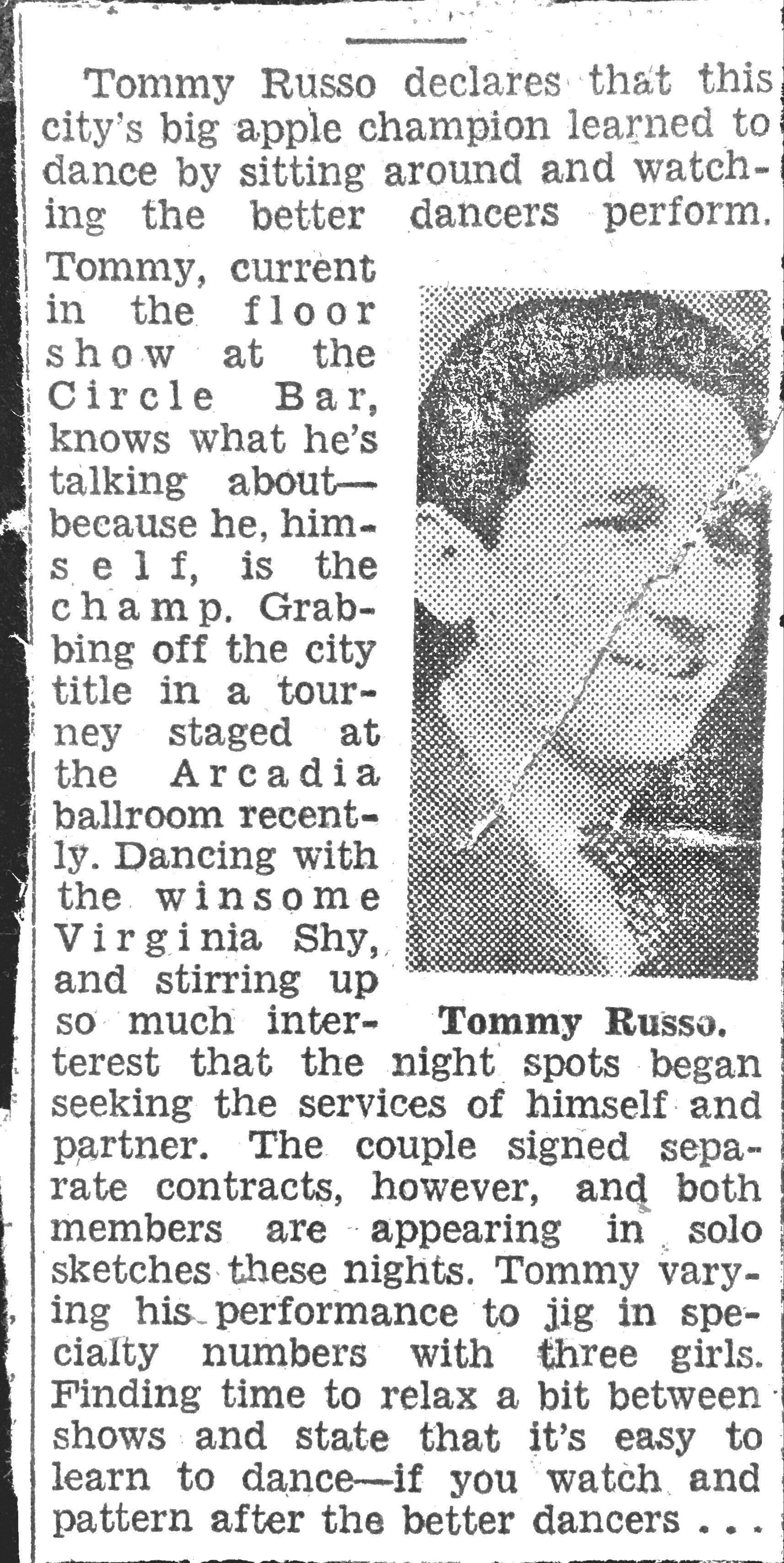

For some dancers in St. Louis, Missouri the open-endedness of the Big Apple went further. In December 1937 a “Big Apple Dance Contest” was held in a series of elimination rounds at Fanchon and Marco cinemas, culminating in a championship at the Granada Theater, a whites-only theater which could seat 1500. Tommy Russo, a first-generation Sicilian-American whose Black neighbors introduced him to dancing via the Charleston and rubber legs, won that championship title with Ruby Kindred. He said that contestants could dance “whatever you wanted . . . the shag, boogie woogie, peckin’ . . . just like any other contest.” There was no caller, and the words on the marquee and the apples on the women’s skirts are perhaps the only changes to what was otherwise called a “Dance Contest,” or a “Collegiate” division of a dance contest. The win led Kindred and Russo to paid dancing gigs in nightclubs.

Perhaps most fascinating is Russo’s description of the “Big Apple” he led in collaboration with bandleader Tony Di Pardo at the sumptuous Arcadia Ballroom in St. Louis’ Grand Center:

“When we started the Big Apple, the couples, they already know . . . what they’re going to do, [the band] got their music all set up. We’d go over by the bandstand, and I’m leading them, and I’m leading them to the center of the dance floor. As we move to the middle of the dance floor, we make a circle. Ok, the band’s playing, now say you’re doing the waltz, you get out there, the music knows what you’re going to do, so they play waltz music. Then the other ones do the shag, they come out, and do the shag, and the music plays the shag. They, uh . . . boogie woogie, you know all that, whatever dance they do, the music would follow. And, you know, you get in the middle of the circle, and that’s the way we did the Big Apple. And after that, everyone did their thing, the band really played, everybody marches off [gestures to opposite corners] to where they go.”

If you share the reaction I had when Tommy first relayed this to me, halfway through that paragraph a voice in your head said, “Wait–waltz?” Yes, the so-called Big Apple at one of St. Louis’ grandest ballroom was a fairly straightforward exhibition put on by the Arcadia’s best dancers. Among the ten or so couples involved with this performance, which Russo says they did nightly for a period of time, also included a tango couple, whom Tony Di Pardo’s band was prepared to accommodate. Attempting to assuage my bewilderment, Russo said, “That’s what we did here in St. Louis . . . In the East Coast they probably done it different, I don’t know, I’ve never been up in the East Coast or West Coast.”

Arcadia Ballroom, St. Louis Other newspaper articles in St. Louis comment on requests made to a bandleader to begin calling the Big Apple, and a North Carolinian leading a Big Apple at the Hotel York, but Tommy Russo’s account offers a larger lesson in the naming of dances and their real-time ambiguity and regionality, which soften as dance fads firm up in a collective looking back.

The phenomenon of Shag, which is strongly tied to the rise of the Big Apple, may also have more to do with variation in regional terminology than it does with stylistic cohesion during the swing era. In his documentary Rebirth of Shag, Ryan Martin explores such regional variations that existed before Collegiate Shag became centered on a six-count, or “double rhythm,” basic. White ballroom baron Arthur Murray certainly played a role in codifying this version of shag, which he did jointly in exploiting and codifying the Big Apple, creating a demand for whatever he offered in his studios. (Here’s a good place to acknowledge that while the dance sensation which helped Murray’s studio franchise expand, the Black club whose dancers had birthed said sensation had closed in 1938). Before that, the dance known as Shag from South Carolina was primarily an eight-count, and likely had different names.

More than anything, the Big Apple seemed to secure perennial status for steps like the Charleston, Truckin’, and Suzi-q, and the practice of jam circles and line dances in social dance settings. As the Big Apple craze swept the nation, and by all accounts gave an umbrella term and form to many existing steps, including “shag,” the various partnered swing Charleston steps which were called the finale hop, hop toddle, or flea hop between the mid-1920s and mid-1930s in St. Louis, simply became known as shag.

Mysterious Connections: The Little Apple and St. Louis Shag

A compelling feature of the Little Apple, a subsidiary of the Big Apple danced by only two partners, is a side-by-side Charleston step that includes (varyingly) triple steps, kicks, and stomps. A few clips from Hollywood movies reveal the connection: two youngsters who demonstrate “the Big Apple” for Jimmy Stewart and Jean Arthur’s characters in the 1938 film You Can’t Take It With You swing out of the gate with a scuff, kick, step, hop, run, run, and a triple-step. In the middle of a choreographed series of swing-Charleston variations, Johnny Downs and Eleanor Lynn mix in a kick, and, kick, and, kick, step, triple-step as they dance in the 1938 short It’s In the Stars. No doubt, these elements had been circulating among dancers like riffs among musicians, but for reasons likely not tied to national dance trends, they congealed into the stylized swing Charleston that came to be known as St. Louis Shag.

Shannon Butler, a third-generation Shag dancer and instructor in Minnesota, fascinated me recently by recounting the first time she had danced with St. Louis swing dancers Valerie Kirchhoff and Dan Conner in the 1990s. As Butler recalled, when Conner initiated a side-by-side position and started dancing St. Louis Shag, she thought, “oh, he’s doing the Little Apple”: another lesson about how our names and categories for dance systems are ever-shaped by regionality, temporality, culture, and memory.

Works Referenced

“‘Big Apple’ Dance Craze Is Spreading.” The Indianapolis Star, 17 October 1937, pg. 57.

“‘Praise Allah’: The Big Apple Dance is Rising and Shining.” The Morning Call, 23 August 1937, pg. 9.

Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois, 1996.

Dancing the Big Apple 1937. Directed by Judy Pritchett. 2011.

“Roosevelt Thinks The Big Apple is Lacking in Rhythm” and “Young Roosevelts Entertain 500 at White House Ball.” The Daily Times. 31 December 1937, pg. 8.

“‘Big Apple’ New Dance Craze Originated in Vacant Church.” Aiken Standard. 4 August 1937, pg. 2

“Medley of Dances, Old and New Make Up Dance, ‘The Big Apple.’” The Pittsburgh Courier, 11 September 1937, pg. 13.

Keep Punchin’. Directed by John Clein. 1939.

Russo, Tommy. Interview. Conducted by Christian Frommelt. 18 February 2011.

“Winners Named in Three ‘Big Apple’ Elimination Contests Here”. The St. Louis Star Times, 13 December 1937, pg. 17.

“‘Big Apple Contest to Be Staged by Theaters Here.” The St. Louis Star Times, 26 November 1937, pg. 23.

“Joe Bardgett, a breezy gent . . .” The St. Louis Star Times, 4 December 1937, pg. 9.

The Rebirth of Shag. Directed by Ryan Martin, 2014.

You Can’t Take It With You. Directed by Frank Capra, featuring Jean Arthur and Jimmy Stewart. 1938.

It’s In the Stars. Directed by David Miller, featuring Eleanor Lynn and Johnny Downs. 1938.

-

The Rendas: First Generation Immigrants Dancing Swing in St. Louis

by Christian Frommelt

Eva (nee Giaraffa) and Joe Renda, born in 1922 and 1923 respectively, were life-long St. Louisans and purveyors of the dialects of swing dance known today as Imperial Swing and St. Louis Shag. As children of Sicilian immigrants growing up near Downtown St. Louis’ Little Italy district, the Rendas’ story resonates with a larger narrative of immigrants whose love for dancing with jazz became a part of their identity in the United States.

Like Tommy Russo, the Rendas grew up in the the populous area radiating from Carr Square just north of Downtown St. Louis where Eva’s father, Carlo Giaraffa, sold coal and ice to the neighborhood using a spruced-up horse and cart and Joe’s family operated a grocery and meat market, and also sold spaghetti and other goods to regional roadhouses.

The Thomas Rizzo Produce Stand at the Union Market near Carr Square exemplifies the initial occupation for many Sicilian immigrant families. Missouri History Museum Photographs and Prints Collection. Block Brothers Photographic Studio ca. 1919. While at the time the neighborhood may have appeared immoveable, 96 percent of the households on North Ninth Street, in the heart of Little Italy, had changed occupants between 1921 and 1926. For most, the enclave served as a sort of halfway house, not a fixed destination.

It’s no surprise that occupants made any effort they could to move out of the overcrowded and unsanitary district. Many Italian immigrants opted to move to The Hill, a neighborhood which remains one of the most resilient Italian immigrant enclaves in the United States (and which will be explored in a future post through the story of dancer James Merlo) while others, like the Rendas, moved outward, north and west, from Downtown as they became more affluent. Today scarcely more than the street names bear any resemblance to Downtown’s former northside immigrant hub.

While constant change defined the urban landscape and one’s place in it, dancing offered social cohesion for young second-generation immigrants. Dances sponsored by fraternal organizations such as DeMolay International and the Elks, as well as high school hops, enabled young adults to socialize, Joe recalled. As devotees of swing music, his friend group graduated to dances in the ballrooms, including The Riviera Club, owned by political giant Jordan Chambers, the “Black Mayor of St. Louis.” The Rendas described learning with friends and by watching the best dancers, many of whom competed in Big Apple contests on movie theater stages and ballroom floors.

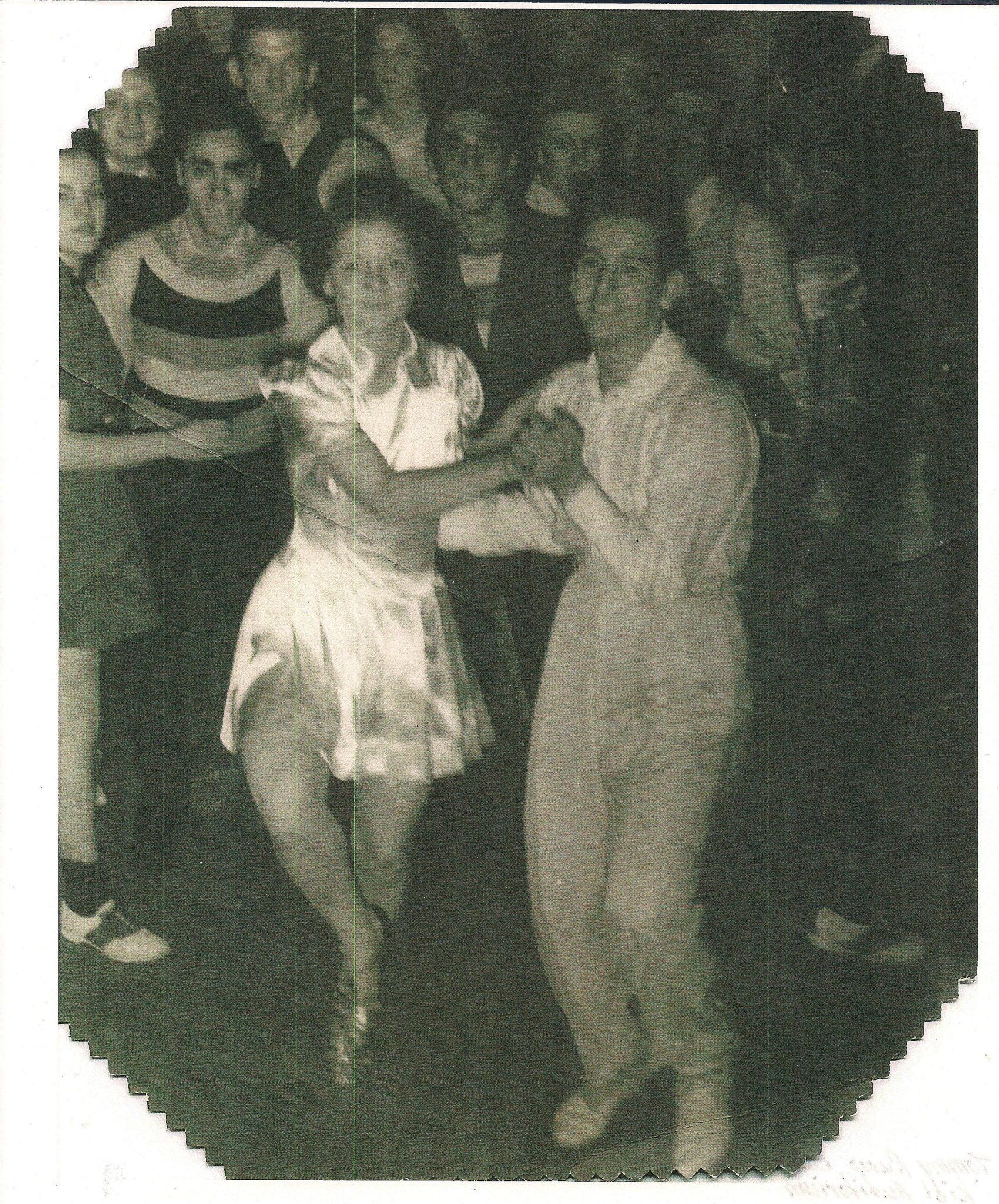

Mike Renda and Virginia Shy competing in Springfield, Missouri One such contestant was Mike Renda, Joe’s older brother by two years, and a prize-winning swing dancer in St. Louis during the late 1930s. In fact, when Mike was drafted to serve in the Army in 1941 he was working as a “prancing usher” at the reputable Loew’s Theatre, a gig he may have landed through winning dance competitions. Mike regularly partnered with Ruby Kindred as well as Virginia Shy, who won the Big Apple Championship with Tommy Russo, another second-generation Sicilian from Carr Square, in 1938. Mike Renda and Virginia Shy are pictured in an iconic Shag pose–knees up, smiles wide, and Mike’s index finger pointed skyward–after taking 2nd place in a jitterbug contest in Springfield, Missouri in 1938. Tragically, Mike was killed in World War Two in 1944.

Joe was also drafted into the army in 1941 and was stationed as a radio and searchlight operator in Canoga Park, California, near Hollywood. Incidentally, this put him within hitchhiking distance to the celebrity-infused Lux Theater and the Palladium Ballroom, where he could social dance to bands like Harry James’ on Monday nights. He also remembers walking by Lucille Ball as she worked in her home garden.

After the war, “we danced constantly,” Eva recalled. She worked in a dress-making factory, and Joe worked at Universal Film Company and they started dating while going out to the grand ballrooms such as the Club Plantation, modeled after Harlem’s Cotton Club, featuring Black artists for a white-only clientele. As legend has it, Duke Ellington met Jimmy Blanton in St. Louis after Blanton had performed at the Club Plantation with the house band, the Jeter-Pillars Orchestra. Tune Town (formerly the Arcadia Ballroom), which hired sought-after traveling bands like Count Basie for week-long engagements, was another hot spot for swing enthusiasts like the Rendas.

In 1948 Joe and Eva were married and held their reception at Northside Turner’s Hall in the Hyde Park neighborhood of St. Louis (a decade later jitterbug champion Teddy Cole would host dances at the Northside Turner’s Hall featuring Ike Turner and His Rhythm Kings). The Rendas spent the next several years raising a family and managing a Dairy Queen franchise, among other business ventures, before Joe began a long-term career at McDonnell Douglas, which became part of Boeing aerospace manufacturers.

Many of the ballrooms folded in this post-war era, shrinking both the size of the bands and the venues that held them. Still, the Rendas remained active, even competitive, dancers and music enthusiasts, befriending the Gateway City Big Band, jazz educator Charlie Manese, and musician Jim Bolen, who frequently invited Eva and Joe to dance with the band at venues such as the Casa Loma Ballroom as an extension of the band’s performances.

The Rendas after competing at the Roseland Ballroom in New York in 1992

In 1992 the Rendas competed in a nation-wide swing dance contest for dancers aged 50 and above. The contest was part of the Geritol-sponsored Big Band Bash featuring music by singer Helen O’Connell and the Jimmy Dorsey Orchestra. The Rendas won the regional qualifying contest in Chicago, Illinois, and advanced to the Grand Finals at the Roseland Ballroom in New York City where they competed against seven other couples. Eva was 70 and Joe was 68, and they placed 3rd. Amusingly, the winners of the previous year’s Big Band Bash in 1991 were famed swing dancers Marge and Hal Takier from Los Angeles.

Here is a clip of the Rendas discussing their interpretation of the Shag and how skilled dance partners could make it a “show-stopper,” so long as they were rhythmically unified with the band and with one another. Joe passed away in November 2019 and Eva in April 2020, ages 95 and 97 respectively, making these interviews all the more invaluable.

Special thanks to Diane Renda, daughter of Eva and Joe, for providing key biographical details and for giving permission to use family photographs.

Works Referenced

- Renda, Eva and Joe. Interview. By Christian Frommelt. January 21, 2012.

- Renda, Eva and Joe. Interview. By Christian Frommelt and Jenny Shirar. January 7, 2012.

- Mormino, Gary Ross. Immigrants on the Hill: Italian-Americans in St. Louis 1882-1982. University of Missouri Press. 2002.

-

“Every Night, Twice on Sundays”: The Story of St. Louis Swing Dancer Tommy Russo

By Christian Frommelt

During the first few decades of the twentieth century rows of tenement houses radiated west from the Mississippi River and north from the garment district of Downtown St. Louis. The city contained more than two and a half times its current population. A near constant fog of coal smoke darkened the sky, assassin gunfire of feuding mobsters and bootleggers riddled the air against the brassy melodies of Bauer’s Band or Sirli’s Band in the crowded neighborhood parks, and youngsters smoked cigars on street corners while selling Post Dispatches and Globe Democrats. Newly arrived African-American migrants from Mississippi, Russian Jews from New York, immigrants from Poland, Greece, Ireland, and Sicily clustered in an entrepreneurial ground zero packed with food markets, barbershops, restaurants, and saloons. Here, near the intersection of 8th and Carr Streets, is where the story of swing dancer Tommy Russo begins.

In 1908 Russo’s future neighborhood was the most densely populated of any seven contiguous blocks in the city and the Civic League of St. Louis decried its squalid living conditions and overcrowding, comparing it to the tenements of New York City in 1860. Most buildings were only two or three stories tall, each lot consisting of a front-facing house, a rear house–sometimes a converted stable–making the alley “practically another street,” and often a third “middle house” between the front and rear addresses. The neighborhood was referred to variously as the heart of the foreign section, the poverty district, and the Lung Block, referring to the prevalence of tuberculosis deaths.

“That’s what I thought life was. I thought that was it,” Russo, born in 1916, recalled. He was the second oldest of nine children to Vincenzo and Antonina Russo (née Lamantia), who immigrated from around Palermo, Sicily at some point in the early 1910s, and whose names appear as James and Lena in U.S. census records. According to the 1920 census the Russos lived at 818 Carr Street and James was a peddler of a fruit bus, which Tommy explained was common for Italian immigrants:

“Let’s say out of ten persons persons—the Italian people—nine of them . . . they sell fruit and vegetables. They had a stand. My dad had a pushcart; he’d push it from North St. Louis to South St. Louis, around the neighborhood, hollering ‘tomatoes’ and all that. There was quite a few of those, you know, pushing . . . with two wheels, just pushing ’em . . .”

African Americans who danced nightly on their porches (which for six or seven months out of the year was the best living space of a cold water flat) near Jefferson and Washington Avenues caught the eye of adolescent Russo who wandered the city streets freely. This intersection, just around the corner from Scott Joplin’s first permanent residence in St. Louis, was mere blocks from the junction of Chestnut Valley and Mill Creek Valley, an epicenter of Black business and the cradle of ragtime and blues music in St. Louis’ Central Corridor. Chestnut Valley stretched west from the Booker T. Washington Theater where Josephine Baker won a Charleston contest and, as a street dancer with the Jones Family Band, ascended to Shuffle Along in New York City. Dancers in this neighborhood taught Russo his first steps, the Charleston and rubber legs, in the mid-1920s, which would form the basis of his repertoire in Shag, Lindy Hop, and, later, the all-encompassing Big Apple.

Such transmission of dance and music idioms from Black Americans to white European immigrants was commonplace at places like the legendary integrated Savoy Ballroom in Harlem, New York, where a young Jewish dancer named Sol Rudusky emulated pioneers such as Shorty George Snowdown before changing his name to Dean Collins and moving to Los Angeles. Early exchanges like this lay outside prescribed social channels like dance academies, and in many cases white dancers would go on to gain recognition in spaces that barred Black people from entry.

“I’m tellin’ ya, I used to dance every night, twice on Sundays.”

As Russo’s dance recognition swelled he befriended tap dancer Rufus McDonald, who aided Russo by installing taps on his shoes, taught him tap basics and the Shim Sham, a wildly popular stage routine, which swing dancers adopted as a social line dance akin to the later Electric Slide. McDonald, known generally as “Flash,” and “Snow White” in local advertisements, went on to great success in 1943 as a long-time member of the Four Step Brothers, the first dance group, and the first Black tap dance troupe, to be honored on a commemorative star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Throughout the 1950s and 60s the Four Step Brothers performed on the Ed Sullivan Show, and in televised performances with Jerry Lewis, Dean Martin, Perry Como, and others. McDonald was a life-long St. Louisan until his death in 1991.

A photo of The Four Step Brothers with Rufus McDonald on the far left addressed to the Russo family and signed “Snow White.” Roughly between 1938 and 1941 Russo and McDonald performed floor shows together in clubs like Steve Cady’s, located at the present-day KDHX 88.1 FM radio station in Grand Center. As a professional entertainer Russo sang, danced, trained chorus line dancers, and held dance tournaments. He emceed floor shows that packaged popular music, trending dances, and comedy for dining audiences. Along with his older brother, singer-comedian “Jumpin’ Joe” Russo, wife-to-be Helen “Dixie” McGrane, and Rufus McDonald, Russo performed in the “Prevues of 1941” at the Empire Ca-ber-et at Delmar and Taylor. He performed also at Club Boulevard, located under the left field bleachers of Sportsman’s Park at North Grand and Dodier, the original home to the St. Louis Cardinals baseball team.

In 1941 Russo was enlisted into the Army during World War II and worked at bases in California, Washington, and Alaska. By the end of his service in 1945, he had married Dixie and they were expecting their first child. Although the couple continued to perform sporadically in the late 1940s, raising a family had replaced jitterbugging. Russo briefly owned and operated a music nightclub called the Beachcomber on South Kingshighway in the 1950s, and then worked for the Local 520 as a cement finisher.

I met and interviewed Tommy in 2010 when he was a spry 94 years old. In addition to his incredible anecdotes from bygone neighborhoods and ballrooms, he taught me about the wide breadth of rhythmic and spatial variations he and his peers employed. In his demonstrations he widened my perception of St. Louis Shag as being a core of side-by-side basics, kick aways, and fall-off-the-logs to include back-to-back figures, added foot taps to elongate basics, and consistent on-beat running steps or kicks that could support any variety of dynamic shapes. Perhaps even more importantly he taught me about the unfixed nature of dances-as-named. “They may have called it Shag. All I cared about was that they liked it,” was his response to my insistent questions about the names of steps.

In 2011 Tommy Russo graced the Nevermore Jazz Ball & St. Louis Swing Dance Festival, where he social danced, sang “All of Me,” with Meschiya Lake’s band and performed the Shim Sham at the Casa Loma Ballroom. He noted wistfully how these were his stomping grounds close to 80 years earlier.

Tommy Russo (1916-2014)

Big thanks to Gayle Werner, Tommy Russo’s daughter for facilitating interviews and sharing her father’s scrapbook with me.

Sources and Further Reading

Mormino, Gary Ross. Immigrants on the Hill: Italian-Americans in St. Louis, 1882-1982. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986.

Miyatsu, Rose. “Rediscovering St. Louis’ Lung Block” https://history.wustl.edu/news/rediscovering-st-louis’s-lung-block. Washington University Department of African-American Studies. May 8, 2019.

Prince, Vida “Sister” Goldman. That’s the Way It Was: Stories of Struggle, Survival and Self-Respect in Twentieth-Century Black St. Louis. History Press, February 5, 2013.

Rumbold, Charlotte. Housing Conditions in St. Louis: Report of the Housing Committee of the Civic League of St. Louis. The Civic League of St. Louis, 1908.

Russo, Tommy. Interview. Conducted by Christian Frommelt. 1 December 2010.

Russo, Tommy. Interview. Conducted by Christian Frommelt. 7 December 2010.

Russo, Tommy. Interview. Conducted by Christian Frommelt. 18 February 2011.

-

Before Shag They Danced Finale Hop, Flea Hop, and the St. Louis Hop Toddle

by Christian Frommelt

There is magic in performing swing dances in public. Inevitably, some audience members will themselves be dancers, or carry with them the legend of how their parents met dancing in one of the old ballrooms. Following a demonstration of several swing dance styles at an Eden Seminary concert series in St. Louis County in 2016, two members of the audience approached me. They introduced themselves as Vernon and Marge Wagner and recalled their dancing years at the Casa Loma Ballroom. Then Vernon told me that what we had identified as the “St. Louis Shag” they use to call the “Hop Toddle.” I jotted the enchanted term down and filed it away.

Years later I was digging through period newspapers and found out that the Hop Toddle, also known locally as Finale Hop and Flea Hop, was a St. Louis-based variant of partnered Charleston and inspired a popular dance called the St. Louis Hop. These dances, with names faded like beer ads across the city’s corridors of brick, some stretching for miles and others missing entirely, prelude the aspect of swing dancing called Shag in St. Louis.

The Backdrop: African American Artists Set New Standards in Popular Dance Through the Texas Tommy and the Charleston

Shag and adjacent swing dances, even when using European conventions of partner dancing, are rooted within the African American vernacular jazz idiom. Music critic Albert Murray states, “Blues-idiom dance movement being always a matter of elegance is necessarily a matter of getting oneself together,” and that its distinctive character is a “unique combination of spontaneity, improvisation, and control.” In this context dancing involves, among many things, a steady rhythm, a dynamic relationship between partners, musicians, and audiences, and a social dance context that includes “rituals of resilience and perseverance through improvisation in the face of capricious disjuncture.”

During the ragtime and jazz eras tens of thousands of Black people migrated from Southern states to St. Louis fleeing racial terror to build centers of economic and communal strength. Their dances, of course, migrated too. At the same time an influx of European immigrants filled tenement districts near or overlapping centers of Black business and entertainment. Street corners, porches, hole-in-the-walls, and dance halls were a reprieve from the stifling aspects of life. Some of the most skilled white dancers–often second-generation immigrants–learned directly from their Black neighbors or acquaintances, a partial, sometimes brief, breech in the hardening geography of enforced American segregation. Many more, however, would learn disembodied elements of Black dance forms through performances and dance classes in whites-only facilities. Ultimately, generations of folks of all backgrounds would come to champion swing dancing as their pastime, even as their way of life.

Most available primary sources relevant to early jazz- and swing- dances in St. Louis are white newspapers where the context of African-American vernacular jazz idiom is lost or distorted. Acknowledging the wider context of Black dance innovations rising to the national stage in the early 1900s can help to offset distortions and illuminate “new” jazz-era dances as being adaptations on a longstanding continuum.*

The Texas Tommy

Texas Tommy Dancers dancing to Sid LeProtti’s Band in San Francisco in rare film, probably in 1914. The story of the sensational Texas Tommy dance, which bridged the ragtime and early jazz eras, provides some key context around emergent jazz- and -swing-era dances throughout the United States. The Texas Tommy has eponymic origins but was made famous in Black dance halls along the Barbary Coast in San Francisco sometime in the first decade of the 20th century. Broadway impresario Florence Ziegfield’s interest in showcasing the dance in New York arose out of excitement around San Francisco’s appointment to hold the next world exposition. Between 1912 and 1913 Mary Dewson, Ethel Williams, and Johnny Peters were among the Black artists who showcased the up-tempo Texas Tommy in major cities, helping to encase such rigorous rhythmic propulsion and death-defying control of centripetal force on which future partner dances would be based. As Williams recalled, “. . . there were two basic steps—a kick and hop three times on each foot, and then add whatever you want, turning, pulling, sliding.” She also drew a clear connection between the Texas Tommy and the Lindy Hop.

As an exhibition dance, the Texas Tommy rivaled dances which traveled in a counter-clockwise line-of-dance and gave enthusiasm for new “spot” dances that favored rhythmic complexity and individual expression over a partnership’s spatial position on the floor. The Texas Tommy dance reflected a synthesis of African-derived rhythmic sophistication and European-derived music harmony and counterpoint as a recent American musical standard—ragtime—pioneered by Black Americans in the Central United States, came to shape popular music.

Texas Tommy Dancers arrive in St. Louis in 1912 The Charleston

In 1923 American popular dancing forever changed when musician James P. Johnson and choreographer Elida Webb staged the Charleston, a dance imported to New York City by the Geechee people of the Carolinas, in the Broadway Show Runnin’ Wild. Whether identified as the Geechee Dance or presented anonymously through dozens of variations and extensions, the Charleston bridged the jazz and swing eras and became an essential building block of Shag.

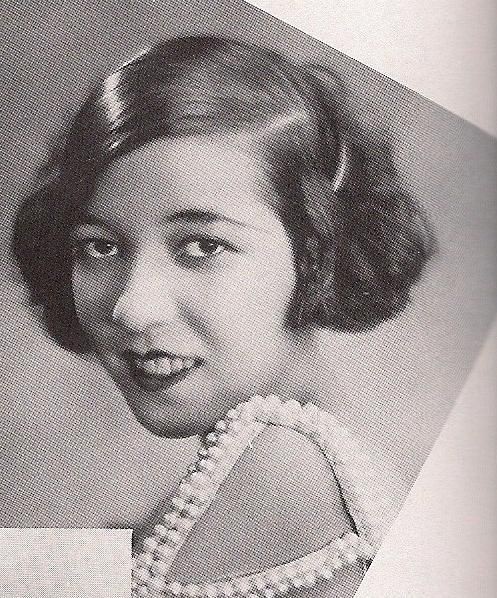

Elida Webb Finale Hop and Hop Toddle of St. Louis

“Innovations consist of the Friday night ‘finale’ and ‘toddle hop’ dance competitions that are soon to displace the Charleston if they have not already done so,” reported the St. Louis Globe Democrat in mid-June 1926 from St. Louis’s largest open-air dance floor at the Forest Park Highlands amusement park.

The trend of the Toddle Hop, or Hop Toddle, began more than a decade before the term “Shag” was widely used outside of the Carolinas, and primary sources suggest that it was a sibling of the earlier Finale Hop, a dance named after the Finale Hoppers of Brooklyn who were said to have bounced from the last songs of one dance hall to the next to avoid entrance fees. While “toddle,” stepping with an on-beat bounce, and “hop” were general terms for dancing to jazz music, evidence suggests that the Hop Toddle was an identifiable stylization of competitive partnered Charleston in St. Louis.

In September 1926, at the beginning of a new dance season, an advertisement for the Arcadia Ballroom’s dancing school announced, “Learn the ‘Valencia’ and new ‘St. Louis Hop Toddle.’” At the same time, the Black-owned Booker T. Washington Theatre not far away hosted a weekly juvenile Charleston contest and brought to St. Louis the latest dances and songs circulating the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA) entertainment circuit. This is how artists like Josephine Baker could interact with national talent, and land traveling stage work that led to New York City and beyond. Ballrooms, dance schools, and theaters facilitated a constant exchange of national and local dance trends—an endless game of terpsichorean telephone.

A city-wide championship in Finale Hop was held in the final months of 1926 at local movie theaters with music by Gene Rodemich, one of the leading jazz band leaders in the region. Prize money and salaried dance positions were awarded to contest winners, elevating the competition but also serving to funnel elements of Black dance forms into segregated white spaces.

In Alton, Illinois, a river town about twenty miles north of St. Louis, dancers shared a competitive bent for dancing and participated in Finale Hop prize contests as late as 1933. An H.A. Stecker told the Alton News Telegraph in 1968, “I came along first at the end of ragtime when jazz was first born and the one step, foxtrot, and hesitation waltz brought on a new breed, ‘The Old Smoothies.’ Then came the Charleston and the hop toddle followed by the rhumba, tango, and the cha cha. I did them all.” This account reveals, along with my interaction with the Wagners, that Hop Toddle, tethered to the Charleston, remained in the dance consciousness of the St. Louis region decades after the jazz and swing eras.

St. Louis Hop: “A Dance That is Supposed to Have Originated in St. Louis”

In July 1926 The Metropolitan Theater in Los Angeles was staging performances and contests featuring a “new dance craze,” conducted by banjo extraordinaire Eddie Peabody. As leading performer Clarice Ganon stated,

The Metropolitan Theater in Los Angeles ‘The St. Louis hop’ . . . is a dance that is supposed to have originated in St. Louis. It is taking the place of the Charleston. It is a mixture of the Negro shuffle and the Charleston. The hop is danced to a syncopated rhythm double the time of the Charleston. There is lots of movement in it. Folks who are not fast with their feet are advised to shun it.

(Let’s be clear: white publications used the term “Negro shuffle” previously to describe both the Foxtrot and Charleston when those dances were new to activate a lens of exoticism, not to describe a tactile dance movement). Once again, a dance marketed as a threat to the Charleston proved instead that the reign of the Charleston endured, and that the emblematic high-speed footwork of Shag was in circulation.

Dance historian Forrest Outman first relayed to me that Finale Hop may have evolved into St. Louis Hop, and indeed, a July 1927 letter to the editor in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch says, “Los Angeles was overwhelmed with the ‘St. Louis Hop,’ a dance which originated in this little old town of ours and is better known here as the ‘Finale Hop.’ This dance took hold of Los Angeles as strong as the Charleston took the country and was all the rage out on the coast.” The writer closes with a wistful prayer for Congress to “put the Hops back in our once world-famous breweries.”

St. Louis Hop was documented in writing. The sheet music for “The Original St. Louis Hop: Flea Hop or Fox Trot” includes instructions sung to the melody of the song: “Hop to the left, twice on your left foot while your right foot’s clogging—Then do the same thing to the right, clog with the left,” and “After a hop you do a kick but keep your partner clogging—Feet crossed until you change or decide to stop.” The last page of the sheet music shows the feet of a dance team executing further variations and positions, “as arranged by Benda,” a classical stage dancer in San Francisco, with enigmatic and contradictory written instructions. Regardless, the central hopping and clogging steps echo the Texas Tommy and coheres with other late 1920s partnered dances that incorporated tap dance elements and emphasized athleticism and speed. Similar contemporary dances such as the Prep Step, Hoosier Hop, and the Varsity Drag were featured in films. Ultimately, the hops, kicks, cross steps, and “clogs” in circulation at the cusp of the swing era would become the shared vocabulary of St. Louis Shag.

In Betty Lee’s Dancing: All the Latest Steps (1927) Lee describes another version of St. Louis Hop with basic footwork as all slow steps (taking two beats each), starting with four toddling steps (walking with a bounce), followed by four step-hops, upon which one can add leg swings to the sides and forward and back. Lee also directs partners to turn in unison while doing this mirrored footwork. These shapes resemble what we would identify as closed-position Collegiate Shag more than St. Louis Shag today.

These two published instructions of the dance share little in common, and to speculate on their connection to the Hop Toddle and Finale Hop championed on the floor of the Forest Park Highlands in St. Louis is to daydream. What the publications do illustrate is that St. Louis Hop became a buzzword that stage performers and ballroom instructors used to extend and deepen demand for the Charleston and its derivatives before the term Shag was widely used.

Flea Hop: The Shag of the 1920s?

For present-day swing dancers, “Flea Hop” often describes a six-count rhythm that features step-stomps, a vestige of the pre-swing era Flea Hop, another byword for up-tempo jazz dancing. Dance historians such as Lance Benishek and Peter Loggins have cited the mysterious Flea Hop as a precursor to the styles that became known as Collegiate Shag.

A few years after the obsession with Finale Hop and St. Louis Hop, two St. Louis ballroom instructors made remarks linking the dances to Flea Hop, which stands as a qualifier in the subtitle of the “The Original St. Louis Hop” song. In 1930 local ballroom instructor Ann Clark recounted a trip she took to Los Angeles where after seeing Eddie Peabody perform at the Metropolitan Theater she read an announcement for an upcoming St. Louis Hop contest: “My California friends couldn’t understand that I, a dancing teacher, had not the slightest idea what the widely advertised St. Louis Hop was. Needless to say, I was in the first row the day the contest opened and you can imagine my surprise when I found the St. Louis hop no other than the flea hop which had originated in our own ballroom.”

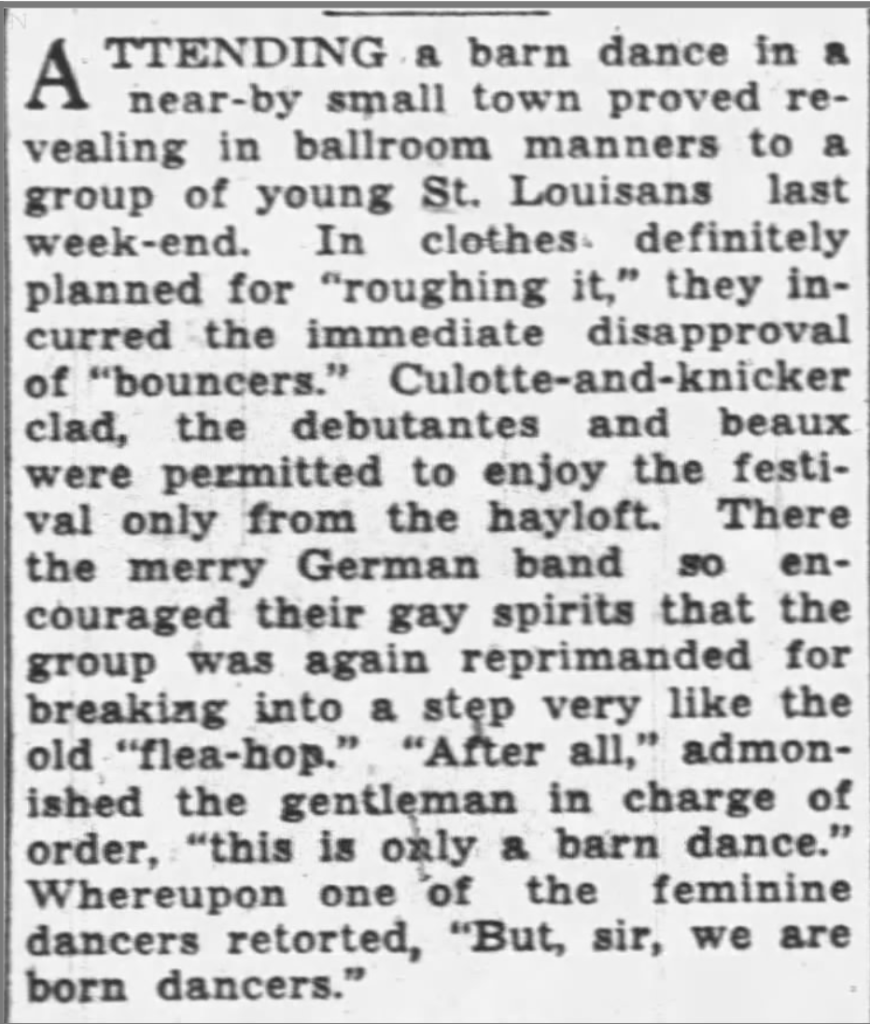

May 1936 – a lovely reference to the lively Flea Hop, as well as a charming pun that uses a St. Louis accent (in which “born” would be pronounced “barn”). Harry Trimp, another local ballroom instructor, recalled that after the Charleston, “New steps were constantly in demand, and the next dance to run riot in St. Louis was the hop toddle. This was a hop with a redowa step and eventually developed into the flea hop, which was extremely popular.”

In the same breaths, Trimp confessed that young people, not ballroom instructors, set dance trends, further revealing that Finale Hop, Hop Toddle, or St. Louis Hop as dances named and marketed were flavors of the broader lived reality of people who danced, as Albert Murray says, “to meet the basic requirements of the workaday world.”

When another dance known as “The Shag” radiated outward from the Carolinas with the Big Apple craze in 1937, that term took on a larger meaning and joined the ranks of the Texas Tommy, Lindy Hop, and Charleston—dances difficult to describe, but easy to recognize. What preceded the naming or packaging of these dances was a public demand for dance beat-oriented music and an endless stream of on-beat hops, kicks, scuffs, turns, and crossovers passed down and improvised on the continuum of Black-American vernacular dance, adopted, adapted, and practiced by working class people writ large.

By the mid-twentieth century Shag in St. Louis congealed into a system of side-by-side basics, kick-aways, fall-off-the-logs, front-to-back sliding doors, whatever stomps and kicks pleased the dancers, and whatever extensions the partners felt could spellbind competitors and audiences.

Notes

*The continuum of African American vernacular dancing over the centuries is profoundly illustrated by Moncell Durden’s documentary Everything Remains Raw and brought to life by the dancing of Latasha Barnes and others in the Jazz Continuum.

Acknowledgements

Big thanks to Latasha Barnes and Jenny Shirar for reviewing early drafts and providing necessary insights. Thanks to Forrest Outman help contextualizing dances of the period, particularly Finale Hop.

Works Referenced

Lee, Betty. All the Latest Steps. 1927.

Murray, Albert. Stomping the Blues. University of Minnesota Press, 2017

Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois, 1996.

Robinson, Russell and George Wagner. Original St. Louis Hop Flea Hop or Foxtrot sheet music. Villa Moret, San Francisco, 1926.

Stearns, Jean and Marshall. Jazz Dance: The Story of American Vernacular Dance. Da Capo Press, 1994.

Sid Leprotti Band, 1914. Website. http://www.jazzresearch.se/upl/website/sid-leprotti-san-francisco/LeProttiFilmResearch.pdf

Strickland, Rebecca, R. The Texas Tommy, Its History, Controversies, and Influence on American Vernacular Dance. Florida State University, 2006.

Newspapers referenced: St. Louis Globe Democrat, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, St. Louis Star Times, Alton News Telegraph, Los Angeles Daily News.