by Christian Frommelt

Albert Murray writes that innovations in jazz music have far less to do with originality, and much more to do with how musicians use counterstatement and variation through existing conventions. What Black dancers in South Carolina did with existing conventions is precisely what made the Big Apple so electrifying to the dancing public in 1937. Not since the Charleston years had a dance held such a capacity to merge exhibition with social participation. The Big Apple possessed siren-like echoes of past dances, from recent Prohibition-era favorites to the African-derived ring shout of coastal Carolina and the square dances of the 19th century. Ballroom instructors and theater managers sought to capitalize on the craze, and the Big Apple, although not enduring, became a huge popular culture reference. The Big Apple’s biggest impact may have been reinforcing the prominence of existing dances and generating a new enthusiasm for “shag” dancing in places like St. Louis.

A Called Dance

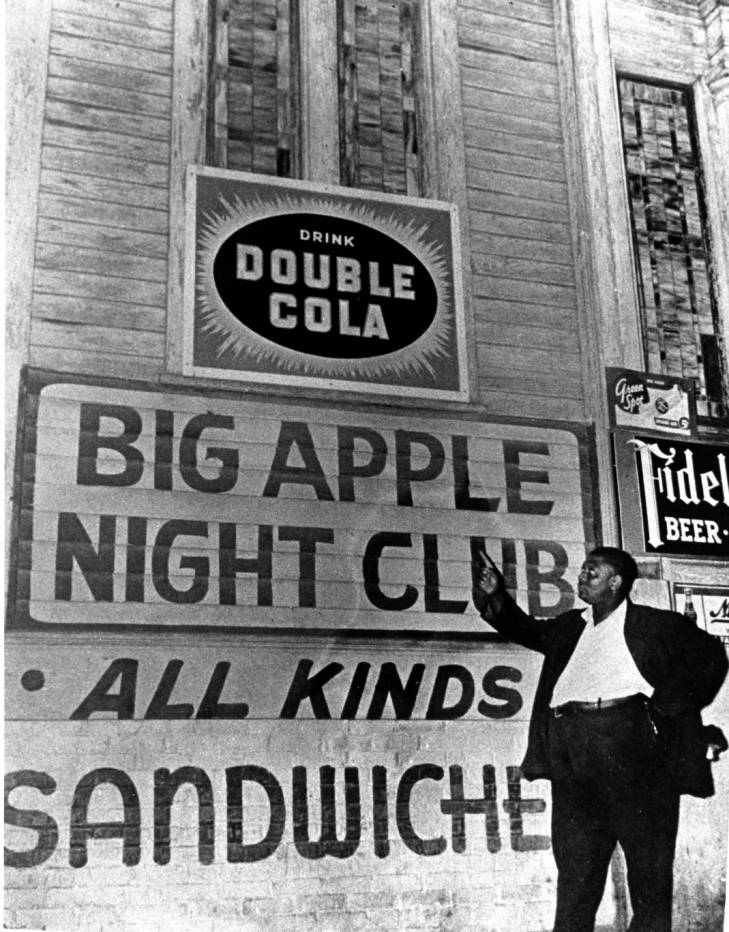

To go to the beginning, or at least a beginning, we must travel to Columbia, South Carolina in 1936 and enter the Big Apple Club, an obsolete Jewish synagogue converted into a Black nightclub managed by Elliot Wright and Frank “Fat Sam” Boyd. Where Orthodox Jewish men had prayed in rows of pews, Black youngsters now held their Saturday night functions. Some nights the club was so full that a queue formed outside of the front door. In a 1937 newspaper article, the 20-year-old Boyd states that clubgoers had been doing the slow drag and one-step for a long time, and that he decided to “step things up lively,” with new figures, which he called by number and were danced by 18 of the club’s expert dancers. According to the article, the figures included Truckin’, Suzie Q, the Charleston, as well as some apple-themed steps, such as “carvin’ the apple,” which involved a series of crisscross steps and fast shuffling.

Group dances that required a caller were widely practiced by Americans of all ethnicities leading up to the 20th century. White ballroom instructors were eager to point out the connections between the Big Apple and traditional European square dances, but African-American dancers had a long-standing tradition of stylizing cotillions, quadrilles, and contradances, which remained popular during the ragtime era. Black professional “set-callers” became reputable for inventing new systems of set-calling and performing original solo steps. When Wright developed new figures to call at the Big Apple Night Club, the convention of calling dances was likely as idiomatic as the old one-step and slow drag.

As an adjacent thought about called dance traditions, I can’t help thinking of how legendary jazz dancer Frankie Manning would call out the steps of the Shim Sham routine on a floor full of swing dancers. The fact that most had memorized the routine didn’t matter. The way he called the steps enlivened a new sense of how they should be executed. The eagerly anticipated “slow motion” and “freeze!” calls during the free-for-all portion of the routine forged new creations only partially within one’s control.

From the Big Apple Club to the White House

The version of the Big Apple that quickly spread to white coastal beach resorts in the spring of 1937, and then on to large stages and ballrooms in New York, was a version as imitated, interpreted, and adapted by white teenagers. Elliot Wright allowed Billy Spivey, Donald Davis, and Harold Wiles to sit in the balcony, where they could watch the dancers. It was a microcosm of the legally enforced racial modus operandi that allowed white dancers to siphon off Black dances into spaces of opportunity to which white folks alone were privileged. Soon enough entertainment scouts began holding contests and staging the Big Apple at grand theaters like the Roxy and across the vaudeville circuit. By the end of 1937 the Big Apple had been performed by 500 children at the White House, where President Roosevelt claimed that it “lacks rhythm.”

In many ways, the Big Apple’s newness was merely in its name-branding. Wright told the Aiken Standard in August 1937 that “We call it a swing dance, the white people call it the Big Apple.” And the Pittsburgh Courier describes an already-familiar lexicon of Harlem jazz dancing:

“you break right into the good old Charleston–After a bit of that you catch the ork [?] on the down beat and switch gracely into the ‘Black Bottom’–then grab your armful and go to town via the Lindy Hop route;–but not for long because the Shag comes next and as if that isn’t enough ya jam it with a bit of the Suzi-Q that was the thing just last season ago–Then not to miss anything ya sweet-on it with just so much of the ‘Truck.’ After that you should be good and tired and down to the very core of the ‘Apple,’ so ya . . . glide into a bit of fox-trot . . . . If [you] can think up any other steps, add them also for according to the best authorities on the subject . . . anything goes when you’re doing the ‘Big Apple.’”[2]

In other words, in the context of swing, the Big Apple was everything and the kitchen sink, incorporating favorite steps like Truckin’, classics like Black Bottom, but also leaving room for new inventions of rhythmic movement, spatial configuration, and imitation with steps inspired by boxer Joe Louis and tap dancer Fred Astaire. The key ingredient of “shining” required individuals to bring their own style, creativity, or imitation to the benefit of the group, an element of the jam circles made legendary by the lindy hoppers of the Savoy Ballroom. It’s fitting then that Frankie Manning’s Big Apple choreography featured in the 1939 film Keep Punchin’ enshrined a temporary dance fad into the enduring story of jazz dance.

When the Big Apple Came to St. Louis

For some dancers in St. Louis, Missouri the open-endedness of the Big Apple went further. In December 1937 a “Big Apple Dance Contest” was held in a series of elimination rounds at Fanchon and Marco cinemas, culminating in a championship at the Granada Theater, a whites-only theater which could seat 1500. Tommy Russo, a first-generation Sicilian-American whose Black neighbors introduced him to dancing via the Charleston and rubber legs, won that championship title with Ruby Kindred. He said that contestants could dance “whatever you wanted . . . the shag, boogie woogie, peckin’ . . . just like any other contest.” There was no caller, and the words on the marquee and the apples on the women’s skirts are perhaps the only changes to what was otherwise called a “Dance Contest,” or a “Collegiate” division of a dance contest. The win led Kindred and Russo to paid dancing gigs in nightclubs.

Perhaps most fascinating is Russo’s description of the “Big Apple” he led in collaboration with bandleader Tony Di Pardo at the sumptuous Arcadia Ballroom in St. Louis’ Grand Center:

“When we started the Big Apple, the couples, they already know . . . what they’re going to do, [the band] got their music all set up. We’d go over by the bandstand, and I’m leading them, and I’m leading them to the center of the dance floor. As we move to the middle of the dance floor, we make a circle. Ok, the band’s playing, now say you’re doing the waltz, you get out there, the music knows what you’re going to do, so they play waltz music. Then the other ones do the shag, they come out, and do the shag, and the music plays the shag. They, uh . . . boogie woogie, you know all that, whatever dance they do, the music would follow. And, you know, you get in the middle of the circle, and that’s the way we did the Big Apple. And after that, everyone did their thing, the band really played, everybody marches off [gestures to opposite corners] to where they go.”

If you share the reaction I had when Tommy first relayed this to me, halfway through that paragraph a voice in your head said, “Wait–waltz?” Yes, the so-called Big Apple at one of St. Louis’ grandest ballroom was a fairly straightforward exhibition put on by the Arcadia’s best dancers. Among the ten or so couples involved with this performance, which Russo says they did nightly for a period of time, also included a tango couple, whom Tony Di Pardo’s band was prepared to accommodate. Attempting to assuage my bewilderment, Russo said, “That’s what we did here in St. Louis . . . In the East Coast they probably done it different, I don’t know, I’ve never been up in the East Coast or West Coast.”

Other newspaper articles in St. Louis comment on requests made to a bandleader to begin calling the Big Apple, and a North Carolinian leading a Big Apple at the Hotel York, but Tommy Russo’s account offers a larger lesson in the naming of dances and their real-time ambiguity and regionality, which soften as dance fads firm up in a collective looking back.

The phenomenon of Shag, which is strongly tied to the rise of the Big Apple, may also have more to do with variation in regional terminology than it does with stylistic cohesion during the swing era. In his documentary Rebirth of Shag, Ryan Martin explores such regional variations that existed before Collegiate Shag became centered on a six-count, or “double rhythm,” basic. White ballroom baron Arthur Murray certainly played a role in codifying this version of shag, which he did jointly in exploiting and codifying the Big Apple, creating a demand for whatever he offered in his studios. (Here’s a good place to acknowledge that while the dance sensation which helped Murray’s studio franchise expand, the Black club whose dancers had birthed said sensation had closed in 1938). Before that, the dance known as Shag from South Carolina was primarily an eight-count, and likely had different names.

More than anything, the Big Apple seemed to secure perennial status for steps like the Charleston, Truckin’, and Suzi-q, and the practice of jam circles and line dances in social dance settings. As the Big Apple craze swept the nation, and by all accounts gave an umbrella term and form to many existing steps, including “shag,” the various partnered swing Charleston steps which were called the finale hop, hop toddle, or flea hop between the mid-1920s and mid-1930s in St. Louis, simply became known as shag.

Mysterious Connections: The Little Apple and St. Louis Shag

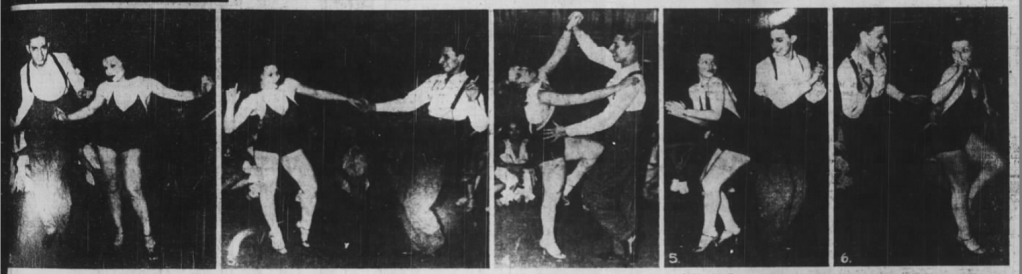

A compelling feature of the Little Apple, a subsidiary of the Big Apple danced by only two partners, is a side-by-side Charleston step that includes (varyingly) triple steps, kicks, and stomps. A few clips from Hollywood movies reveal the connection: two youngsters who demonstrate “the Big Apple” for Jimmy Stewart and Jean Arthur’s characters in the 1938 film You Can’t Take It With You swing out of the gate with a scuff, kick, step, hop, run, run, and a triple-step. In the middle of a choreographed series of swing-Charleston variations, Johnny Downs and Eleanor Lynn mix in a kick, and, kick, and, kick, step, triple-step as they dance in the 1938 short It’s In the Stars. No doubt, these elements had been circulating among dancers like riffs among musicians, but for reasons likely not tied to national dance trends, they congealed into the stylized swing Charleston that came to be known as St. Louis Shag.

Shannon Butler, a third-generation Shag dancer and instructor in Minnesota, fascinated me recently by recounting the first time she had danced with St. Louis swing dancers Valerie Kirchhoff and Dan Conner in the 1990s. As Butler recalled, when Conner initiated a side-by-side position and started dancing St. Louis Shag, she thought, “oh, he’s doing the Little Apple”: another lesson about how our names and categories for dance systems are ever-shaped by regionality, temporality, culture, and memory.

Works Referenced

“‘Big Apple’ Dance Craze Is Spreading.” The Indianapolis Star, 17 October 1937, pg. 57.

“‘Praise Allah’: The Big Apple Dance is Rising and Shining.” The Morning Call, 23 August 1937, pg. 9.

Malone, Jacqui. Steppin’ on the Blues: The Visible Rhythms of African American Dance. University of Illinois, 1996.

Dancing the Big Apple 1937. Directed by Judy Pritchett. 2011.

“Roosevelt Thinks The Big Apple is Lacking in Rhythm” and “Young Roosevelts Entertain 500 at White House Ball.” The Daily Times. 31 December 1937, pg. 8.

“‘Big Apple’ New Dance Craze Originated in Vacant Church.” Aiken Standard. 4 August 1937, pg. 2

“Medley of Dances, Old and New Make Up Dance, ‘The Big Apple.’” The Pittsburgh Courier, 11 September 1937, pg. 13.

Keep Punchin’. Directed by John Clein. 1939.

Russo, Tommy. Interview. Conducted by Christian Frommelt. 18 February 2011.

“Winners Named in Three ‘Big Apple’ Elimination Contests Here”. The St. Louis Star Times, 13 December 1937, pg. 17.

“‘Big Apple Contest to Be Staged by Theaters Here.” The St. Louis Star Times, 26 November 1937, pg. 23.

“Joe Bardgett, a breezy gent . . .” The St. Louis Star Times, 4 December 1937, pg. 9.

The Rebirth of Shag. Directed by Ryan Martin, 2014.

You Can’t Take It With You. Directed by Frank Capra, featuring Jean Arthur and Jimmy Stewart. 1938.

It’s In the Stars. Directed by David Miller, featuring Eleanor Lynn and Johnny Downs. 1938.